What are novels for ?

"What are novels for ?", Sade asked over two centuries ago.

Radicals often have a ready reply: "I don't care much for novels !" The genre is dismissed as boring, cliché-ridden, bourgeois or petty-bourgeois, a distraction from the real thing. Except... there are exceptions. The radical usually has his own selective pantheon of books purporting to be of informative or possibly subversive value: for instance, in the 20th century, from a variety of points on the political compass, a wide range of novels from B. Traven to "radical noir".

The question is how much or how little can fiction contribute to a critical understanding of the world.

Let's take a look at Cara Hoffman's novel So Much Pretty, first published in 2011. (1)

TOO BRIGHT FOR HER OWN GOOD ?

Though most of So Much Pretty takes place in 2009 in Haeden, a small town in upstate New York, the plot spans 17 years: numerous flashbacks refer to events between 1992 and 2008, and a multiple narration gives voice to different and opposed characters, completed by pieces of evidence and audio files.

The main character, Alice Piper (aged 16 in 2009), is a child prodigy and I.Q. genius: she is physical, imaginative, creative, top of her class, an expert swimmer, and finds the time for volunteer hospital work: "an achiever", with a touch of the unreal: "Never herself, she was a frog, a mermaid, a bird." In adult life, she could have been anything: scientist, artist, athlete, academic high-flyer, eminent ecologist... Until 2008, when things start to slip.

"DIMINISHING EXPECTATIONS"

Gene and Claire Piper are socially concerned doctors. Gene worked in the corporate world for two years until he had enough, and Claire found herself unable to help and cure damaged or raped women in a New York Comprehensive Free Clinic. She "hated herself, hated her job, hated everyone. [..] The way it was done would never be enough." Both fell short of what they expected, so they moved to Haeden's rural life in 1995. Now Claire earns a modest living by proofreading medical books, and Gene by organic farming: "diminishing returns for our diminishing expectations", Claire calls it. "Living the solution", "living off the grid" in the hope that "soon everyone would be living off the grid" are what's left of dashed radical hopes. Journalist Stacey Flynn cruelly remarks that Claire and Gene have "experienced too many bedtime readings of Peter Pan ". It is unclear whether Alice questions her parents' quest or their disillusionment - both, likely.

The Pipers, living on their farm in Haeden, get help from their friend Constant, although his job in Big Pharma means "manipulating people into doing something [he thinks] is wrong". The Pipers' "poverty and grandstanding were actually based on privilege [because trying] to convert people to organic farming [..] was subsidized by wages coming from a pharmaceutical company" Constant hated.

"DARKEST SIDE OF THE OBVIOUS"

The Pipers have come to an area where sustainability and biodiversity are unwelcome. Haeden's life depends on agro-business, run by another family, the Haytes.

Like the severed human ear lying in a field in Blue Velvet, there's a dark side to Haeden, but contrary to David Lynch's Lumberton, Haeden has no seedy criminal underworld: danger comes from the apparently innocuous economic world. The whole area turned "from a self-contained farming village to a service-industry bedroom community", when in the 1990s, Haytes became a subsidiary of a globalised Dutch company : thousands of cows, and offices round the world. Jim Haytes "gets things done", and likes neither welfare recipients nor "outsiders". Unlike Alice Piper, Dale, Jim's son, (aged 22) is no intellectual: he works for his father's business and travels to Europe a couple of times a year. He has both charm and authority, a 22-year old businessman everyone likes. Dale considers himself in love with Wendy, a waitress at The Alibi, but everything suggests he just fancies her and takes her for granted. He tells Wendy "a man can only take so much pretty walking back and forth in front of him", as if she was too attractive for her own good.

Haeden could have proved the right place for an ecological thriller with journalist Stacy Flynn as the whistle blower: she "believed articles in the newspaper could change the way the world worked." After some success in local reporting in Cleveland, she "felt [her] future as a 1940s-style muckraker" would be secure if she found in Haeden a real break thanks to "a big investigative piece". She believes she has material for a major environmental scandal: a large waste site which has serious health effects on the population. What Haytes' industrial farming produces is not just milk, it's also shit, which most likely contaminates the local water.

Murder, however, not ecology, will be So Much Pretty's red thread. Neither the Pipers nor the Haytes are dysfunctional families, but extremes are going to come to the fore on both sides, setting in motion a climactic chain of events.

(GUN) CULTURE

As befits Alice's multiple talents, her school essays are out of the ordinary. She writes on Lesbian feminist Monique Wittig's Les Guérillères (1971), where woman warriors have overthrown patriarchy. Alice reads it as "an epic poem and a memorial to the dead": better "utter a death rattle than to live a life anyone can appropriate". In Wittig's novel, women are no more "givers of life", but "bringers of death".

The truth is, Alice is dissatisfied with books. Referring to Beauvoir, Wittig, ecologists, etc., she comments: "I'm sick of reading about things." And: "I am alone. I am totally alone."

Not quite. Alice has a strong relationship with Ross, a local she goes hunting rabbits with, and he teaches her how to shoot. Soon Alice is as good with a gun as an expert marksman. Ross, the American "loner" back-to-nature type, thinks learning to shoot at the age of 10 is better than being "brainwashed" at school. While non-violence and gun-control are not among Alice's main tenets, a sense of self certainly is. Her school essay on the Situationists cares less about the 1968 general strike than about a critique of everyday life in the name of freedom and autonomy.

Some people are aware of a streak of instability in Alice. "Her lack of fear was disturbing", a friend of her parents says.

NO-ONE IS INNOCENT

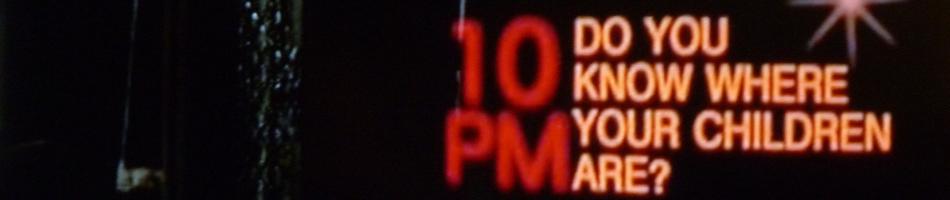

Wendy, the waitress at The Alibi, goes missing in Fall 2008, is found dead in a ditch in April 2009, her corpse shows evidence of having been kidnapped, locked up, abused and raped, the plot unfolds from there, and there is no way we can now avoid spoiling the ending.

When searching for Wendy, Alice puts forward a "cost-benefit analysis" which chills her parents: "Does finding Wendy benefit her family and the town more than the difficulty or fear or whatever takes from the town ? [..] what's practical is almost always ethical." After the body is found, she writes to her closest friend Theo (a year older than her) : "I think I have fallen through the hole in all the logic of the entire world and I see now that nothing holds up and I feel that I am going to keep falling." Alice asks Theo to burn the letter.

When Wendy corpse is dug up, she thinks back on her parents' expressions she grew up upon: "Beneath the paving stones, the beach", "Demand the impossible"... She now regards them as "axioms of an underground and unrealized wish. Today is the day I stop wishing". There is no beach : "only bodies and bones".

The Haeden community prefers to think that the crime cannot have been committed by locals, and the police do not look too closely at the Haytes. For her part, Alice is convinced that the Haytes brothers and their mates are responsible for Wendy's ordeal. She finally walks into the school in disguise (it's Spirit Day, everyone is dressed up) and kills seven teenagers. In her mind, anyone who might have known about the rape is complicit, so she targets the boys who preyed on Wendy. But she also shoots a guiltless male bystander.

Alice believes the Haytes brothers are guilty because of their attitude. She lacks definite proof, and her only evidence is sexist words and body language: but is this an admission of guilt, or male sexist bragging ? Alice identifies the culprits not by what they did (she cannot know for sure), only by the way they behave, i.e. circumstantial evidence which could not stand in court, but Alice is not bothered about the Law.

Alice comes under suspicion, but there is no concrete evidence. Pending the outcome of a still inconclusive enquiry, she is remanded in custody. Interviewed by Flynn, she confesses to the murders: those she killed "knew where Wendy White was" and did nothing to save her. "People who would do this would probably do other things that are ethically wrong and costly for the community." So "I wouldn't call it an act of revenge. I would call it an act of rationality. It's clearly eliminating a problem."

The journalist now has everything she needs... "And nothing". She deletes the interview.

Alice manages to be transferred to a hospital, and then escapes with Theo's help. Up to now, their relationship has been intense, they are not lovers, but understand each other perfectly, they share secrets, and sometimes write in code. He knows there is something borderline in her. Three years before, "he was afraid of who she would become without him".

Eventually, Alice's parents move out of Haeden, looking out for possible jobs with Doctors Without Borders, taking with them their stock of radical books (Situationist International included). It is up to the reader to decide whether coming to Haeden was a radical failure for Claire and Gene Piper: and was it one from the point of view of their daughter's upbringing ?

Also leaving are Stacy Flynn the journalist and Tom the ambulance driver and nurse, who are now living together. Flynn will not be awarded a Pulitzer price for her investigating skills. Contrary to the hero-of-our-time journalist who unmasks crooked politicians, exposes scandals and reveals what society really is, Flynn only discovers the truth to decide to cover it up.

Six years later, Theo and Alice are living in California, and will probably have a child together some day. She needs Theo as a "counterweight" to her over-dynamic personality. So far, they have evaded detection.

NOVEL, SOCIAL NOVEL & CRITICAL NOVEL

The modern novel arose as the story of the individual "free" to move within society. Even when there is a collective subject, it is nearly always represented by distinctive characters. The novel focuses on the experience of protagonists largely unfettered by the constraints that used to bind Ancient and medieval heroes to tradition, religion, family and community. The modern hero has to make sense out of his/her life and find his/her own way in an uncertain world. From the 17th century to our time, from Defoe to Jane Austen to Virginia Woolf to Philip Roth, forced freedom is the predicament of the novelist's main characters.

So inevitably novels also offer a social and historical portrait, which often comes as a critique of society (Dickens, Hugo, Zola, Dos Passos, Steinbeck... especially in "science-fiction", for example Ursula Le Guin), and The Trial is as politically meaningful as Gatsby or Radclyff Hall's Well of Loneliness.

"The classic novel grew up and grew strong upon ideas and arguments provoked by public issues, politics, religion - the questions of Free Trade, empire, women and so forth. It was assumed that a serious novel would deal with such questions in their bearing upon themes of power, money, sex and class." (Candace Bushnell)

Dealing in what way ?

Few novels take a direct political stand, like Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin against slavery. Usually, social awareness is implicitly dramatised via fictional characters. Engels was not unique in thinking that, despite Balzac's "reactionary" monarchist views, his Comédie Humaine could be read as "the real history of France from 1815 to 1848". Social division and conflict are the undercurrent of many 19th century novels, Elisabeth Gaskell's for example, but the subtext of nearly all plots does not suggest a classless society, rather a class-inclusive one, Hugo's peuple at last reconciled with themselves, and who no longer have the right of insurrection once they have the right of suffrage. Dickens was an acute observer of the suffering caused by the Industrial Revolution, but he stood for reform brought about by well-meaning businessmen and politicians.

In the 20th century, social critique grew more explicit (Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Sinclair Lewis, Richard Wright, Alan Sillitoe...), with the progress of the "problem novel", "protest novel", the proletarian novel"...

The 1930s and 40s introduced the detective as the outsider that reveals the sordid underbelly of modern urban society. E.W. Burnett, Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, Jim Thompson... were contemporary with a militant labour movement, the rise of the CIO, and a growth of left-wing postures favoured by the New Deal.

The world of mass culture is an addition of subcultures and market niches. Even more so in our multicultural age. Since the mid-20th century, a sub-genre of crime novel, "radical noir", has deliberately taken a self-assured far-left (or even anarchist, libertarian communist...) stand. It partakes of the classic ("bourgeois") novel structure, albeit with an antagonistic vision of society. It borrows the code of hard-boiled detective fiction, where the leading figure battles with evil institutionalized corruption in business and police, and applies these conventions to a alleged uncompromising anti-establishment content.

As in the traditional novel, even when a collective subject is emphasised, action is carried out by a central figure who stands out in the crowd, because he or she is the one whose powers and skills overcome conflicts and obstacles: the lead character may be plagued by psychic imbalance, aggressive impulses and even sociopathy, but he/she does what fiction codes expect the champion of a (just) cause to do: reveal and possibly right social wrongs.

In keeping with tradition, the "radical noir" functions on the "heroes vs. villains" pattern. As in mainstream novels, the reader is invited to adopt an empathetic attitude and will support and approve of the key player when he/she identifies with him/her. The 40s and 50s crime fiction left us with the wish that in real life there should be more people like the hero or heroine, more crusading newspaper editors like Bogart in the film Deadline USA (1952). "Radical noir" goes one step further: it professes an outright repudiation of existing society, that supposedly outdoes all previous critiques in print or on the screen.

AIMÉE, LISBETH & ALICE

In the first two pages of Jean-Patrick Manchette's Fatale (1977), cool yet neurotic Aimée has already killed six people (bourgeois hunters). She comes to provincial Bléville, a microcosm of capitalist society (a sort of Doughville or Buckscity, "blé" meaning money in French slang). She befriends the local elite, ultimately murders seven more people, and is finally shot. Meanwhile, the narrator informs us that left-wing capitalist ideology equals right-wing capitalist ideology, we are given a smattering of Marxist and Hegelian references, a baby dies, Aimée hates her mother, we encounter a bishop and a demented baron (though a colourful slightly likeable figure, he also is disposed of), and it remains unclear whether Aimée is a contract killer or plays at being one. Black comedy meets anarchist morality tale.

The year Fatale came out, Manchette (1942-1995) wrote in his diary on April 30: "All in all, I'd rather contribute to communist revolution. For the moment, I haven't succeeded in developing an activity that contributes to it. My only intention is to entertain. My function is to put various things in the spotlights, notably the dissatisfaction and violent reactions to dissatisfaction, inasmuch as these reactions are expressed by the impatient and the backward (the young bank robber, the madman, the terrorist, etc.). Only a scatterbrain can conclude that Marxist, situationist or other categories help to interpret the world and have a revolutionary function because they appear in a book. In our time, the expression of revolutionary thought has to be unitary. The bunch of loosely mismatched categories that appear in my book do not constitute a revolutionary thought, any more than when they appear in France-Soir, Le Monde, or a book by Attali. The extremism of my opinions does not make any difference." (In those days, France-Soir was the best-selling daily; Le Monde was the French "quality" paper, similar to The New York Times or The Guardian, and still is; Jacques Attali is a prolific writer, special adviser to Mitterrand, politician, businessman, etc.)

Manchette was fully aware that his readers could be quite satisfied by the fictionalisation of their own dissatisfaction. Awesome Aimée does not subvert the superhero fantasy that underpins the politics of the thriller genre. Manchette breathes new fiery life into a genre he contributes to : his narrative implies a partial suspension of disbelief that creates a degree of empathetic understanding.

In Millennium, Stieg Larsson's Lisbeth Salander is a rape survivor, a victim turned merciless avenger, who also addresses violence by more violence, but only kills baddies. She is an asocial computer hacker, a vengeful force of nature, albeit for a good cause : her means are not simply justified by the end, they also do not contradict the end.

Alice does the opposite: she addresses injustice with unjustifiable means.

Consequently, though they appreciated the book, some readers took issue with Alice's killing innocent schoolkids as well as the guilty ones: "It's hard to walk away from So Much Pretty without feeling troubled by how the end is resolved", someone regretted. The end was found "upsetting", "certainly scary", "controversial and shocking". Alice's action takes the form of one of the events that receive the largest media coverage: the school mass shooting. Is the reader surprised ? horrified ? awed ?... or all of the above ?

The serial killer and/or multiple murderer has become a fixture in popular culture, especially when he is endowed with substantial intelligence, such as iconic Hannibal Lecter. But Lecter's evil crimes, as gruesome as they are, are vindicated by the fact that he nearly always murders people presented as worse than him (so he appears as a lesser evil), and by his traumatic youth (fed with the flesh of his own sister by cannibal-turned Nazi collaborators in World War II). He is a villain-hero compellingly free from ethics. Besides, precisely because he is a demonised monster, his criminal path is so bizarrely unimaginable that we can safely assume we have nothing in common with him. (Moreover, horror is often mitigated by a pinch of gallows humour : "I'm having an old friend for dinner", the cannibal declares at the end of the film The Silence of the Lambs: no such humorous touch in So Much Pretty). However exceptional Alice is, we can believe in her, which makes her character really troubling: when she deliberately disposes of innocent lives, no extenuating circumstances can diminish her guilt.

Alice is the offspring of a failure and of a tentative reaction against that failure. Her parents compensated for their unfulfilled radical hopes by moving to a place that was inhospitable to an alternative life. Their daughter is a prisoner of her own excellence and of her fierce lucidity - too much reading of revolutionary texts, and trying to make something out of them in an utterly non-revolutionary situation. The final massacre is the culmination of innocence lost combined with idealism gone awry.

Young women could dream of emulating Lisbeth Salander. Alice has no such power of attraction: it is uncommon to fantasise about an Angel of Death.

THE MERITS (& LIMITS) OF AMBIGUITY

Few will seriously read So Much Pretty and close this perplexing book with a self-satisfied smile on their face.

In this story told from multiple perspectives, there's a lot of denial, and self-denial, on the part of the Pipers as much as that of the Haytes. "Every parent's greatest fear", the author explains in an interview, is that her child could be hurt, or (which is a lot more disturbing) that the child herself could hurt somebody, particularly another child.

Unlike propaganda texts and with-a-message-novels, So Much Pretty does not end on a seemingly obvious conclusion: it leaves us disconcerted, faced with Alice's unsolvable challenge. So Much Pretty's ambiguity offers no role model, and implicitly asks us to think for ourselves...

...supposing we so wish to, and that we are in a position to. A fact that bears repeating.

Novels have been compared to a mirror carried along a road, that at one moment gives us a glimpse of a blue sky, and the next a view of a muddy puddle. Reading novels, we look at society through a glass darkly, and the glass reflects surfaces tilted to each other at changing angles. Art echoes the world, its contradictions, its prevailing and also evolving manners, morals and fashions: it does not subvert the world. A statement not as banal as its sounds, considering the widespread belief (even in far-left or ultra-leftist milieus) in the instructive and mind-opening values of various (correctly selected, of course) works of fiction, in print or on the screen. Maybe taking comfort from this belief is due to a present inability (which is ours, too) to "contribute to a revolution" as Manchette said in 1977.

There certainly are life-changing novels, but we do not read novels like essays, textbooks, self-help books, the Bible or Society of the Spectacle: first and foremost we read them for pleasure, not to be informed or educated. The reader wants to be swept in, briefly or not: being outraged and delighted in equal proportions makes for comfortable reading. So Much Pretty is based on a real case, but "I'm not a sociologist. I'm a fiction writer", Cara Hoffman said in the interview. As Jean-Patrick Manchette wrote, whatever "the extremism of opinions", we cannot read into art what is not there.

G.D. (October 2022)

(1) So Much Pretty, published by Simon & Schuster in 2011, and by Windmill Books in 2012.

MORE BOOKS (AND A FEW FILMS)

Other novels by Cara Hoffman: Be Safe I Love You (2014) and Running (2017), by Simon & Schuster. Like So Much Pretty, both centre on a strong woman character, though not as excessive as Alice.

Interview with Cara Hoffman: https: //writerinterviews.blogspot.com/2011/03/cara-hoffman.html

Sade, Idée sur les romans, 1800.

B. Traven (1882-1969), author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1927) most likely took part, as Ret Marut, in the German revolutionary attempts after WW I : Marut, Red : The Early B. Traven:

libcom.org/article/marut-red-early-b-traven-james-goldwasser

Candace Bushnell's quote: Introduction to Mary McCarthy's The Group, Virago Press, 1981.

Engels to Laura Lafargue, December 13, 1883.

Large selection of Marx and Engels on literature and art: www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/subject/art/index.htm

Aloysius P. Dehnert, The Political Views of Dickens, 1947, available on Loyola eCommons

Most of Jean-Patrick Manchette's novels have been published in English by NYRB, and some by Serpent's Tail. In the quote from his diary, "unitary" refers to an essential situationist point: "The revolutionary organisation can be nothing less than a unitary critique of society [..] proclaimed globally against all the aspects of alienated social life." (Society of the Spectacle, § 121) Manchette briefly corresponded with situationists. The year Fatale was published, he wrote in his diary: " what I must never forget: I am the only one (with Mélissa [his partner]) who understands what I do" (April 29, 1977).

Our critique of fiction when it aims to "Educate, Agitate, Organise": Land & Freedom: The Dubious Virtues of Propaganda: Ken Loach's "Land & Freedom": https://troploin.fr/node/82

Other "woman revenge" novels: The Silent Wife, A.S.A. Harrison (2013); Girl on the Train, Paula Hawkins (2015); Our House, Louise Candlish (2018).

Rape vengeance films include Abel Ferrara's Ms. 45 (1981); Steven Monroe's I Spit on Your Grave (2010: the heroine goes as far as killing a male witness who witnessed the rape, took no part, but did nothing to try and stop it); and Coralie Fargeat's Revenge (2017).

Another writer on the fringes of "crime/noir" with strong female characters is Vicky Hendricks: Miami Purity (1995), Iguana Love (1999), Cruel Poetry (2007).

All good people read good books

And your conscience is clear

Tanita Tikaram, Twist in my Sobriety, 1988